Policy Debates Surrounding Rent Regulations

The primary goal of rent control and other tenant protections is, in the short term, to prevent housing costs from spiraling out of control, make rental markets fair and predictable for landlords and tenants alike, and to keep families and low to moderate income residents from being forced to leave their neighborhoods. Over the longer term, the goal is to help create more affordable, stable, and economically and environmentally healthy communities. Many affordable housing practitioners and scholars concur that, when applied with other housing policies geared to eliminating landlord loopholes, and to production and preservation of housing, rent regulations accomplish these goals.

At the same time, with the upsurge in efforts to institute or strengthen and rent regulations, a new —and sometimes old— debate has emerged over the efficacy of these measures. In what follows, we outline some of the main arguments for and against rent regulations.

Its important to note at the outset that there are limitations in the current academic literature on rent regulations. The first limitation is due to the paucity and heterogeneity of contemporary cases to study. Only a few hundred cities in the U.S. have rent regulations today and for those that do, their ordinances vary along with the state policy contexts in which they are based. An additional limitation is that many of the most common “Econ 101” arguments against rent control are based on old studies, premised on assumptions of “strict” forms of rent control, as opposed to the more “moderate” rent control laws common today. Moreover, economic studies that do address actually existing rent control may do so narrowly, eliding the broader policy context.

In an effort to address these limitations, a spate of new studies and literature reviews have been written since the 1990s, giving us a fuller picture of actually existing rent regulations and their impacts. These have been undertaken by public policy and planning scholars, economists, sociologists, as well as practitioners with direct experience in housing and tenant law. We synthesize these studies here, and also hope that to see more research on the topic to fill in persistent gaps.

Why Regulate Rent?

A main argument for protections is that they help redress the power imbalance between landlords and tenants that housing markets create, particularly ones as tight as ours in Santa Cruz and across California. As we know from the game of Monopoly, it is possible for landlords to profit simply from passive ownership of land—whether or not they buy a house or hotel to put on top of it. In a “scarcity market,” meanwhile, when supply is short, landlords can establish a literal monopoly (owning both Boardwalk and Park Place), and profit exorbitantly from this passive ownership. Facing no real competition, and regardless of their investment, they can charge “monopoly rents” and gain windfall profits.[1]

These ever-increasing windfalls—exceeding 50% in five years— put tiny Santa Cruz in league with the most profitable rental markets in the country, according to the National Apartment Association. This in turn gets noticed by large speculative investors—including private equity firms and real estate investment trusts—who buy up local real estate. These outside owners skew the landlord/tenant imbalance even further. Backed up by powerful and well-funded trade groups, like the California Apartment Association, California Association of Realtors, and National Apartment Association, they can advance a real estate-led agenda with elected officials and through marketing campaigns, both locally and statewide.[2]

In this highly unequal political and economic environment, establishing rent regulations and legal protections can help even the playing field—at least somewhat.

A related argument is that such rent regulations are more economically just, given how value in real estate markets is created. We often hear of the secret to success in real estate: “location, location, location.” A multi-million dollar, state-of-the-art beach house on Westcliff would become worthless if it were transported to the middle of the Mohave Desert. And indeed savvy investors are expert in picking good locations, understanding that a house’s “building value” is distinct from the value of the land on which it’s built. Yet what creates the value of that location?

A first answer is that we all do, collectively, as residents. Through our local tax dollars and public sector labor we contribute to local government’s ability to keep our beaches, air, and water clean; plant street trees and repair roads; maintain fire departments, police forces, parks, libraries, public transit, and high-quality schools, from K-12 to Cabrillo to UCSC. Through our local consumption and private sector labor, we contribute to sustaining our craft breweries, surf shops, cafes, bookstores, and music venues. The presence and proximity of these things help create the value of real estate in Santa Cruz. Yet tenants, who constitute a majority of the city’s workers, consumers, and tax-payers, don’t benefit as homeowners do from the value that both help to create. To the contrary, they pay the price for it in escalating rents.

It follows then that policy tools can redress this undue burden. Since housing price increases are so dependent on actions of the public—from infrastructure to amenities to cultural scenes— the public has “a responsibility to limit the passing on of these costs to tenants.” [3] As Pastor et al note, the role of government in producing land value is “one reason why even free-market economists have favored land taxes as a way to sop up excess profits (that is, profits arising from conditions external to the quality of the housing itself) and encourage the more efficient use of land.” As we explore on the history page, this issue became urgent following the passage of Prop 13 in 1978, when California property taxes were frozen for homeowners while “building rents” continued to climb for tenants. Then as now, advocates argue the public has both a right and responsibility to limit this growing inequity between homeowners and renters through regulation.[4]

“Econ 101” Arguments and Responses to Them

Arguments against tenant protections, and rent control in particular, are dominated by older economic analyses. Unfortunately, the view of professional economists on the subject of rent control has been distorted by the mistaken way the concept itself is commonly defined. Referring to an older generation of rent laws, and lacking reference to literatures from urban and housing policy, planning, or law, economists commonly define rent control as, simply, a “ceiling on rents.” Indeed, freshman “Introduction to Economics” textbooks have for decades used rent control as a paradigmatic case of a price ceiling, or a ban on selling a product above a certain price, with its negative effects on otherwise well-functioning markets governed by supply and demand. Through simple diagrams they demonstrate that, capping rents will reduce investment in housing, thereby reducing overall supply, as a result of which prices will go up. Generations of economics students —and faculty— have come to understand the policy in these terms, lending the anti-rent control argument the moniker “Econ 101.” Similarly, the surveys of economists cited to establish consensus on the subject ask whether “a ceiling on rents reduces the quality and quantity of housing.”[5] Defined in this way, it is not surprising that over 90% of economists typically agree. We offer here two main responses to this argument.

The first thing to note is that rent control as currently practiced is not a ceiling. In the U.S., rent control laws mandate “fair returns” on landlords’ investment. Landlords have constitutionally ensured rights to periodic increases in rent to cover operating and maintenance expense as well as cost of living increases, without unduly long delays or lags in these increases. In California, courts have understood these rights in terms of maintaining the income received in the past (Maintenance of Net Operating Income, MNOI), and keeping up with inflation. All cities with rent control in California are required by law to meet these standards. Their rights to do so have been defended in court time and again.[6]

Thus the “consensus” amongst economists is actually on the effects of a rent ceiling, not rent control, and hardly proves their united opposition to the latter. Timothy L. Collins, former Executive Director and Counsel to the New York City Rent Guidelines Board, investigate what happened when economists looked at the actual impact of New York City’s rent control laws rather theory about them. He finds that “economists who have directly examined the impact of [New York City’s rent control law] have thoroughly questioned and criticized the conclusions of those who have considered only abstract models, or only the effects of strict rent control laws.” As one example, he cites Michael Mandel, formerly Business Week’s chief economist, currently chief economist at the Progressive Policy Institute in Washington D.C., who takes issue with the way the policy has been taught: “Economics textbooks, like introductory books in other fields, often engage in oversimplification to make a pedagogical point. In this case, the textbook authors needed a way of illustrating the effects of imposing a price ceiling on a market, and rent control provided a vivid example to liven up the usual dry supply and demand diagram. But good examples can make bad economics.” [7]

A second response to the Econ 101 framework is that housing is not a standard supply and demand driven market. This is particularly true when there’s a chronic lag in the production of affordable housing, as there is throughout California. As noted, rather than a free market, this produces a “scarcity” or “captive market,” with little to no competition or demand-side pressure affecting rents. While landlords can earn windfall profits regardless of their investment, tenants have no recourse but to pay inflated rents or be forced out. And should they leave, they face major barriers to reentering the market. The search can take months and require them to face one or more of the issues we explore on this site: staying local by living in overcrowded conditions, sacrificing basic needs, or accepting major problems with their housing, or moving far away from their jobs, schools, and social networks. This is far from a free market, either on the supply or the demand side of the equation.

Another reason standard supply/demand frameworks are inadequate is the increasingly speculative nature of the real estate market. Value in this market is driven by bets on future profits, and as such is more comparable to a financial market than a supply/demand market in, say, consumer goods. To cite a recent editorial from Los Angeles on this point “Housing prices don’t go up or down just because of how many units we have in the present — if that were the case, all those vacant apartments in Downtown Los Angeles would have “trickled down” to the population living literally right below them on the streets of Skid Row. Rather, the price of housing changes first and foremost because of what people are betting it will be worth in the future.” Increasing supply of market-rate housing will not alter this dynamic.[8]

Anti-rent control arguments also begin with the assumption that rent regulations will discourage new construction. This claim that seems logical: since rent control puts limits on developers’ profits—even if not a total cap— wouldn’t this cause them to divert their investments elsewhere? In fact, the historical evidence for such claims is inconclusive at best. At worst, these claims are deeply misleading, given that there are a number of cities — New York City, for instance — whose largest building booms took place during times of strict rent controls.[9] Further, in California, cities with and without rent control have similar levels of new housing construction.[10] Clearly, a number of factors affect local construction—including the desirability of the location, external market dynamics, availability of public financing, local zoning laws, and the broader policy context at the local, state and federal level. More research is needed to understand how rent regulations—both moderate and strict— interact with these factors, and then how and in what ways they affect new construction.

A related question that has been little researched is the effect of rent control on small, local “mom and pop” landlords as compared to large, corporate landlords. Unfortunately, as noted by Pastor et al., most academic research on rent regulations does not attempt to distinguish between these types of owners. Only a handful have even have tried to define “small-scale,” “mom-and-pop,” or “amateur” landlords. Some suggest that mom-and-pop owners are more likely to charge lower rents and negotiate with tenants, which may mean that, as a group, they are likely less impacted by moderate rent regulations.[11]

That said, more research needs to be done to better understand how rent regulations—again, in combination with other factors— impact real estate values for mom-and-pop landlords. A number of hypotheses could be tested. If rent-stabilized properties are, in fact, offered at a discounted price, as some economists argue, this might make it more feasible for mom-and-pop landlords to enter the market. On the other hand, mom-and-pop landlords may be more likely to abandon properties or allow their units to fall into disrepair, than would larger landlords, due to the real or perceived impacts of rent regulations on their bottom line. Further, given that large corporate landlords enter local markets in order to speculate on and/or flip properties, thus distorting markets for renters, first time home buyers, and mom and pop landlords alike, its conceivable that rent regulations—together with mechanisms like anti-speculation and real estate transfer taxes— could help curb this kind of behavior, to the benefit of smaller local landlords. Further research is required to explore these possibilities.

This points to a larger concern often raised about rent regulations: the prospect that they will cause landlords, in general, to take units off the rental market, thus significantly reducing the supply of rental housing and negatively impacting people seeking to rent. This unintended consequence would certainly be problematic. However, in our review of the literature, together with Pastor et al. and Montojo et al, we find no clear evidence that this would indeed occur, or that it would occur to a degree that would be significant. The case most often cited in that of Berkeley’s passage of rent control in the 1980s, and the “3,100 units” lost in the decade following. The reference here is to Stephen Barton’s history of rent control prior to the passage of Costa Hawkins, in which, using census data, he shows a decline of that number of rental units between 1980 and 1990, representing 26% of Berkeley’s total stock.[12] Yet as he also shows in the chart in which this figure is displayed, during the same period Alameda County and the 9-county Bay Area, where rent regulations were not a factor, lost twice this percentage of rental units: 51 and 52 percent respectively.[13] A comparative study conducted by the Berkeley Planning and Development Department, also citing census data for the 1980-1990 period, showed that the adjacent cities of Kensington, Albany, and Oakland also lost units, demonstrating that “the loss of units turns out to be a general trend in stable census tracts in Northern Alameda County, not something that is unique to Berkeley.” The unit losses in Berkeley were a fraction of a percent more than they were in adjacent cities, and only 1.3% of its total rental housing stock in 1980, which is not a credible argument against rent control. [14]

A further complication in these arguments in that in the period of study in Berkeley, the profits to be made by rentals under rent regulation paled in comparison with those that regulated units would fetch today—in the era of the tech boom. As noted, landlords in Santa Cruz, like those over the hill in the Bay Area, are considered by the National Apartment Association to be reaping the highest profits (or net operating income) in the U.S.. Were regulations to be introduced tomorrow, these profits would not be erased; they only wouldn’t continue to rise as fast. With annual increases and assured return on investment, and no end of demand, landlords would still be doing very well. Thus it is hard to imagine why regulations would drive significant numbers of landlords out of the rental market. A mitigating factor here might be the degree to which fear, peer pressure, and incomplete or inaccurate information —all of which can be spread by anti-rent regulation campaigns when economic stakes are high—will drive market actors to behave in ways that are not necessarily in their economic interest.

Finally, there are inherent limitations to rent regulations, which many opponents—as well as supporters—elide. Rent regulations are not designed to address the problem of affordable housing supply, nor are they capable of doing so. Thus blaming rent control for lack of supply makes little sense. Rather, as we argue throughout the Policy Tools section, a comprehensive approach is required to ensure that tenants are protected while at the same time a sufficient amount of affordable housing is both produced and preserved.

On balance, research shows us that rent regulations still constitute a necessary part of a comprehensive affordable housing solution, even while more research remains to be done. Narrow supply/demand arguments don’t address captive markets or speculation, nor do they count the benefits – social, economic, and environmental —that having stable tenants and communities provide; the costs of displacing tenants and disrupting communities; or the responsibilities of local publics to protect tenants from undue rent burdens. When markets fail, benefiting only a fortunate few, we as a society lose. Thus we have historically seen the need to step in to regulate markets, from antitrust laws in the 1930s that took on monopolies, to living wage laws in the 2010s that have helped to slow escalating inequality. The growing political and economic imbalance between landlords and tenants, as well as impacts of growing rent burdens, overcrowding, unsafe conditions, and displacement, pose a similar challenge and opportunity in terms of developing and strengthening tenant protections.

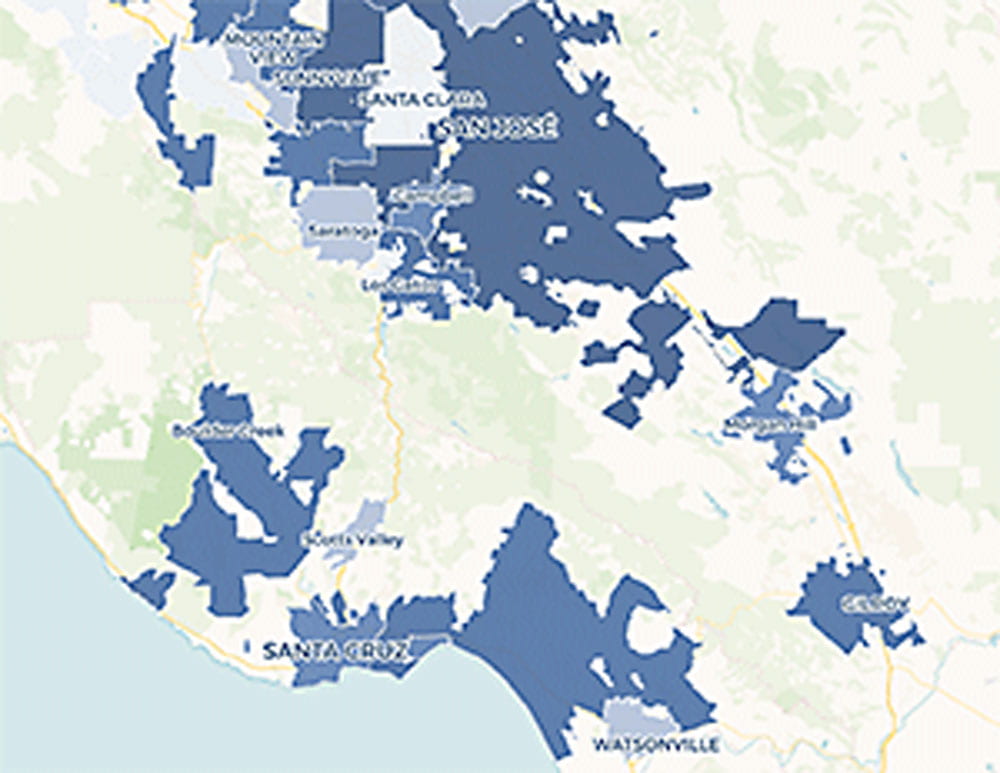

Compare our policies to those of other bay area locations using The Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley’s interactive map.

The three Ps

What are: rent control, rent review boards and just cause eviction protection?

What support services exist for tenants?

Who would be covered?

Why regulate rent?

Econ 101 arguments and responses to them

Early history, 1970s-2010s

The growing rent control movement

Sources:

[1] On scarcity markets see Keating, W. Dennis, Michael B. Teitz, and Andrejs Skaburskis. Rent Control: Regulation and the Rental Housing Market (New Brunswick: Center for Urban Policy Research, 1998), 20; Leslie Gordon, “Strengthening Communities through Rent Control: Case Studies from Berkeley, Santa Monica, and Richmond.” Oakland: Urban Habitat, January 2018. 14; Pastor et al, 7.

[2] See for instance the recent battle over rent control in Santa Cruz: Jondi Gumz, “Santa Cruz rent control foes raise $750,000; supporters raise $38,000.” Santa Cruz Sentinel, October 2, 2018.

[3] On the public’s role in creating land value, see the policy brief and literature review by Stephen Barton, Nicole Montojo, Eli Moore, “Opening the Door for Rent Control: Toward a Comprehensive Approach to Protecting California’s Renters.” UC Berkeley: Haas Institute, 2018, 22-24,

[4] Pastor et al., 2018, 9-10. See also, Stephen Barton, “Land Rent and Housing Policy: A Case Study of the San Francisco Bay Area Rental Housing Market. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 7 (4), pp 845-73.

[5] Frey, Pommerehne, Schnieder and Gilbert, “Consensus and Dissension Among Economists: An Empirical Inquiry,” 74 American Economic Review, 986 (1984); Paul Krugman, “Reckonings; A Rent Affair.” New York Times, 2000

[6] Dennis Keating, Michael B. Teitz, and Andrejs Skaburskis. Rent Control: Regulation and the Rental Housing Market (New Brunswick: Center for Urban Policy Research, 1998), 46. Beyond MNOI, fair-return standards can also include: cash-flow levels, return on gross rent, return on equity,, return on value, and percentage of net operating income. For California’s early Supreme Court decisions, see Dennis Keating, “Rent Control in California: Responding to the Housing Crisis.” Berkeley: Regents of the University of California, California Policy Seminar, No 16, 1983.

[7] Timothy L. Collins, “Rent Regulation in New York: Myths and Facts, Second Edition.” New York State Tenants & Neighbors Information Service, May 2009. Michael Mandel, “Does Rent Control Hurt Tenants?: A Reply to Epstein,” Brooklyn Law Review, vol. 54, 1267, 1268 (1989).

[8] On financialization of rental markets and its destabilizing effects, see Desiree Fields and Sabina Uffer, “The Financialization of Rental Housing: A Comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin.” Urban Studies Vol 53, Issue 7, pp. 1486 – 1502; Tony Samara, “Rise of the Renter Nation.” Homes for All, 2014. ]

[9]Collins, 2009, Ibid, 2. See also studies of cities in New Jersey, which has the highest concentration of cities with rent stabilization, and which find no significant impact on new construction. John I. Gilderbloom and Lin Ye. 2007. “Thirty Years of Rent Control: A Survey of New Jersey Cities.” Journal of Urban Affairs 29(2):207–20.

[10] Leslie Gordon, 2018, ibid.

[11] See John I. Gilderbloom et al. “Intercity Rent Differentials in the U.S. Housing Market 2000: Understanding Rent Variations as a Sociological Phenomenon.” Journal of Urban Affairs 2009. 31(4):409–30; “Maintenance and Investment in Small Rental Properties Findings from New York City and Baltimore” The Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy and Johns Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies, 2013.

[12]Stephen Barton, “The Success and Failure of Strong Rent Control in the City of Berkeley, 1978 to 1995” in W. Dennis Keating, Michael B. Teitz, and Andrejs Skaburskis. Rent Control: Regulation and the Rental Housing Market (New Brunswick: Center for Urban Policy Research, 1998)

[13] Barton, 1998, ibid. 95

[14] “Rent Control in the City of Berkeley, 1978-1994,” Berkeley Planning & Development Department, 1998, 67-74.