A key response to the affordable housing crisis is the production of new affordable housing. Today, there’s a deficit of more than 7.2 million rental homes inexpensive enough for the lowest-income people to afford, and nearly 554,000 Americans are homeless on any given night. Put another way, there are just 35 affordable and available rental homes for every 100 extremely low-income families—those who either live in poverty or earn less than 30 percent of the median income in their area. It’s a problem in every major city and in every state, and for higher income renters as well. Indeed for renters overall, more than half spend more than 30% of their income on rent—the federal threshold for affordability.[1]

It is important to remember that it has not always been this way. In 1960, only about a quarter of renters spent more than 30 percent of their income on housing, half the percentage today. In 1970, a 300,000-unit surplus of affordable rental homes meant that nearly every American could find a place to live. “When there was an adequate supply of housing for low-income people, we did not have widespread homelessness in this country,” says Nan Roman, president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.[2]

California faces the largest deficit of affordable housing in the nation— representing 20% of the total—while Santa Cruz’s deficit is one of the largest in the state. According to 2018 reports by the nonprofit California Housing Partnership and State Office of Housing and Community Development, in order to house low income families without forcing them to spend more than 30 percent of their household income on rent, California needs to build 1.5 million new units, or 25 percent of its total rental housing stock. Santa Cruz County is in need of nearly 12,000 new affordable rental homes, or 27 percent of its total stock. [3, 4, 5]

How do we explain this? As we explore below, over the past century, especially since the political shifts of the 1970s, five major obstacles to producing affordable housing have emerged. This includes: (1) cuts to federal and state spending, (2) shifts in priorities for this funding from multifamily renters to single-family homeowners, (3) increasing privatization and (4) financialization of the housing market, and (5) devolution of responsibility for housing construction to the local scale.

At the same time we are witnessing a resurgence of movements to overcome these obstacles. Many of these aim to increase access to market-based programs – through expanding Section 8, Low-Income Tax Breaks, and Inclusionary Zoning requirements. Others are strategizing for a future in which noncommercial, community-controlled housing takes precedence over private real estate markets. In this alternative reality, “public housing is massively expanded and cooperatives, mutual housing associations, and other nonmarket ownership models take root in cities large and small.” [6] In what follows we discuss these innovative approaches.

Yet, given how long it takes for any new housing to get built, we argue for a holistic approach combining production with protection of current tenants and preservation of existing affordable housing. Otherwise, we risk fueling the crisis through gentrification and displacement while waiting for new housing to come on board.

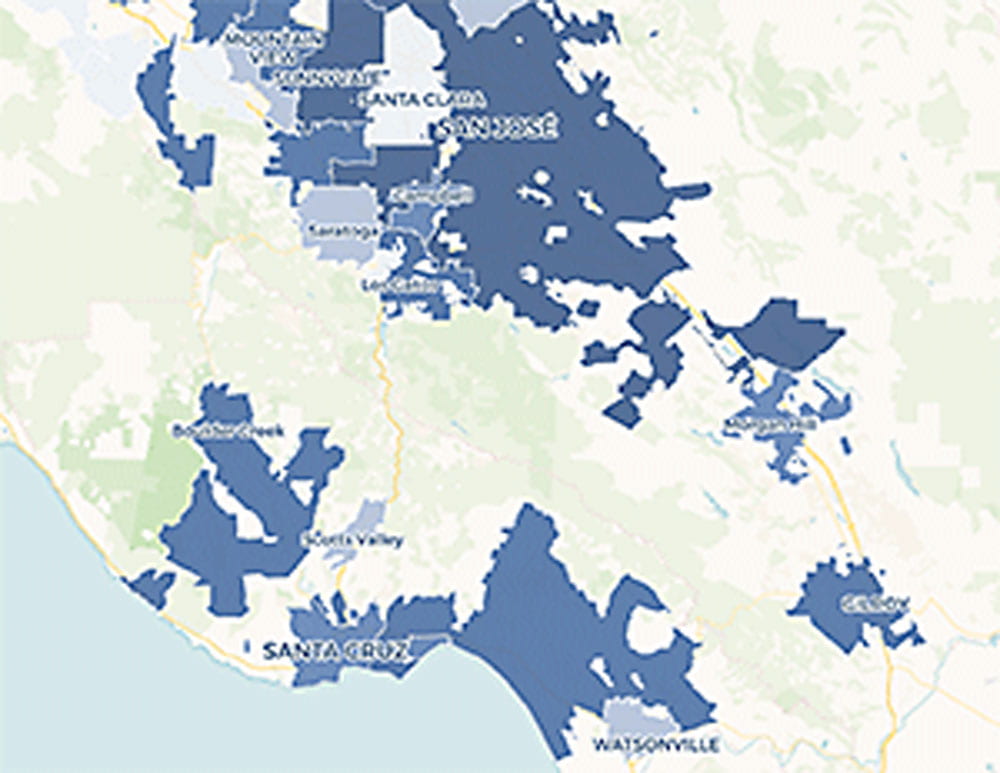

Compare our policies to those of other bay area locations using The Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley’s interactive map.

The three Ps

Reinvestment in Social Housing

Housing Trust Funds

Expansion of Linkage Fees and Bonuses

Affordable Student Housing

Land Use and Zoning

Community Controlled Strategies

Funding Cuts

Shift from Multi-Family Rental to Single-Family Home Ownership

Shift from Public to Private Sector

Financialization

Local Politics

Sources:

- The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes (National Low Income Housing Corporation, 2017)

- Bryce Covert, “The Deep, Uniquely American Roots of Our Affordable-Housing Crisis.” The Nation, May 24, 2018.

- California’s Housing Emergency: State Leaders Must Invest Immediately in Affordable Homes(California Housing Partnership Corporation, March 2018)

- California’s Housing Future: Challenges And Opportunities: Final Statewide Housing Assessment 2025 (California Department of Housing and Community Development, February 2018)

- Santa Cruz County’s Housing Emergency and Proposed Solutions (California Housing Partnership Corporation, September 2018)

- Jimmy Tobias, “Meet the Rising New Housing Movement That Wants to Create Homes for All.” The Nation, May 24, 2018

- Alex F. Schwartz, Housing Policy in the United States. Third Edition. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Schwartz, ibid.

- California’s Housing Future, ibid.

- Schwartz, ibid.

- Susan Fainstein, “Financialisation and Justice in the City: A Commentary.” Urban Studies 1-6. 2016 Special issue: “Financialisation and the production of urban space”

- Betsy Wilson interview, No Place Like Home, April 2018.

- Jennifer Hernandez, “California Environmental Quality Act and California’s Affordable Housing Crisis.” Hastings Environmental Law Journal. Volume 24, Number 1, Winter 2018

- Karen Chapple and Miriam Zuk, “Housing Production, Filtering and Displacement: Untangling the Relationships.” Berkeley IGS: Research Brief. May 2016.

- Miriam Axel-Lute, “New Program Aims to Help Community Land Trusts Get to Scale” Shelterforce, April 27, 2018