Major Approaches to Producing New Affordable Housing

In the face of these obstacles, production of sufficient housing affordable to the low- and moderate income will require a major resurgence of political will and collective vision. Some of the policies discussed below offer a way forward.

Reinvestment in Social Housing

The most important and largest scale form of affordable housing provision has been government subsidized “public” or “social housing.” While under attack since the 1970s, this remains a vital source of housing, and movements have emerged across the country to both protect what exists and to advocate for increased public spending. The movement People’s Action and Homes for All advocate for a massive reinvestment in the budget for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to meet 100 percent of need. Other cities around the world accomplish this: Vienna houses 60% of its residents; Singapore 90%. Its worth exploring how they do this, and the broad social benefits they experience as a result.

Housing trust funds

Housing trust funds are established sources of funding for affordable housing construction and other related purposes created by governments. Housing Trust Funds (HTF) began as a way of funding affordable housing in the late 1970s, after the moratorium on funding for new public housing was introduced. Since then, elected government officials from all levels of government (national, state, county and local) in the U.S. have established HTFs to support the construction, acquisition, and preservation of affordable housing and related services to meet the housing needs of low-income households.

Ideally, HTFs are funded through dedicated revenues like real estate transfer taxes or document recording fees to ensure a steady stream of funding rather than being dependent on regular budget processes. As of 2016, 400 state, local and county trust funds existed across the U.S.

Expansion of Section 8

The housing choice voucher program — aka Section 8—is “the federal government’s major program for assisting very low-income families, the elderly, and the disabled to afford decent, safe, and sanitary housing in the private market.” Housing choice vouchers are administered locally by public housing agencies (PHAs). The PHAs receive federal funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to administer the voucher program. Voucher holders can choose any housing that meets the requirements of the program and is not limited to units located in subsidized housing projects. However, many landlords refuse to accept Section 8 tenants, while insufficient supply of landlords accepting vouchers is the norm across most U.S. cities and counties. In Santa Cruz, the waitlist for voucher holders is 17000 people long. Thus there is a case to be made to try to enlist more landlords into the program as well as to increase the fair market rent threshold in markets with escalating rents.

Expansion of Linkage Fees and Bonuses

Affordable housing impact/linkage fees are charges on developers of new market-rate, residential developments. They are based on the square footage or number of units in the developments and are used to develop or preserve affordable housing. Commercial linkage fees are charges on developers per square foot of new commercial development. Revenues are used to develop or preserve affordable housing.

Density bonuses allow developers of market-rate housing to build higher-density housing, in exchange for having a certain portion of their units offered at affordable prices. In this inventory, we only include a city as having this policy if they allow an additional density bonus beyond that mandated by the state of California.

Mandatory Inclusionary zoning

Inclusionary housing policies require market-rate developers of rental or for-sale housing to rent or sell a certain percentage of units at affordable prices. Several court cases have made unenforceable requirements for affordable rental units within market-rate buildings; by contrast, inclusionary homeownership policies have been upheld in the California Supreme Court. Most concerning is the small percentage of inclusionary units, typically between 10-15 percents, and the fact that developers can pay “in-lieu fees” in place of building the housing; this revenue is used to develop affordable units elsewhere, though is often insufficient.

Community Land Trusts

Community land trusts (CLTs) are nonprofits that acquire and keep land in trust for the long-term benefit of low-income communities, provide one form of permanently affordable, shared-equity homeownership. A community-controlled organization retains ownership of the land, and sells the homes to qualified low-income buyers with a 99-year ground lease. In exchange for the below-market price, the buyers agree to a resale formula that balances permanent affordability over time while allowing them to build some equity as well. The land trust stays involved, assisting homeowners through financial rough spots and acting as a steward of the community asset. Grounded Solutions Network represents the more than 225 CLTs in the U.S. that own around 20,000 rental units and 15,000 homeownership units. Most of these focus on creating permanently affordable housing; some also support multiuse properties and spaces for neighborhood businesses. [15]

Affordable On-Campus Student Housing

There are numerous benefits in having universities based in a city: relatively well-paid and stable jobs; a larger tax base; students who work, consume, and rent locally; and academic programming and research that can infuse the local culture and economy. Yet the presence of a university, particularly in small cities like Santa Cruz, also comes with costs. These are mainly due to the influx of student renters during the school year, and its impact on an already tight housing market, in which students may be competing with local renters for a limited supply of housing. This is of increasing concern in the California towns that house UC campuses, due to the UC’s 2016 unfunded mandate that all ten campuses absorb an additional 10,000 students. What’s more, all ten campuses are expected to take an equal share of these students, or 1000 each, which places higher burdens on small campuses in small cities with limited housing supply, like Santa Cruz and Davis. While UCSC has a record of housing more students on campus than any other UC—53%—this is still inadequate to confront the situation in a town like ours. Thus there are things that we should do to enable UCSC to house more students, and to do so affordably. We take inspiration from groups working on this issue on our campus and at Davis, including the Student Union Housing Working Group, the ongoing Community Advisory Group meetings for the Long Range Development Plan, as well as the UC Davis Taskforce on Affordable Student Housing, Promising ways forward include the following:

Agree to house additional students and employees.

Taking inspiration from the MOU between UC Davis and Yolo County, we support UCSC agreeing to house 100% of all new students, as well as to meet 100% of demand for new employee housing, or face a per-unit fine that goes into a housing fund.

Build more affordable student housing.

Student Housing West is underway. This could be expanded by developing the 2300 Delaware site, which we consider to be the most promising option for new housing—ecologically, economically, and in terms of convenience. Currently dominated by low-rise office buildings and parking lots, this large site could accommodate denser, taller, greener development dedicated to state-of-the-art student housing. The fact that it is a flat infill site, and can make use of existing infrastructure, can help bring down costs. It is well situated on bus lines, bike lanes, and in proximity to the Long Marine Lab, main campus, new commercial development, and open space.

Bring down student housing costs.

For undergraduates, we should adjust UC financial aid budget calculations to reflect actual market value of rental units, rather than individual student survey responses. For graduate students, we should ensure an appropriate ratio between graduate student GSR and TA salaries and housing rates. For both UCSC leadership should advocate for student housing needs at the UC level (in the case of graduate students, these are collective bargaining issues overseen by the University of California.)

Expand funds to support students struggling with housing costs.

The Division of Student Success could launch a Giving Day campaign, and seek other sources of funding from donors and through the development office, to help subsidize student housing and mealplan needs. The campus could increase the emergency loan budget, Slug Support, and support for housing within its “Basic Needs” initiatives.

Advocate for long term solutions.

The university and community can work together, locally and statewide for longer-term solutions. These should respect the needs of local communities in which campuses are based, limit future enrollment increases, and bring an end to unfunded mandates for enrollment growth. Specific goals could include a statewide bond measure and support for state leadership —from the legislature to the governor— who are commit to increasing funding for higher education and student housing needs—including for the UC, CSU and community colleges.

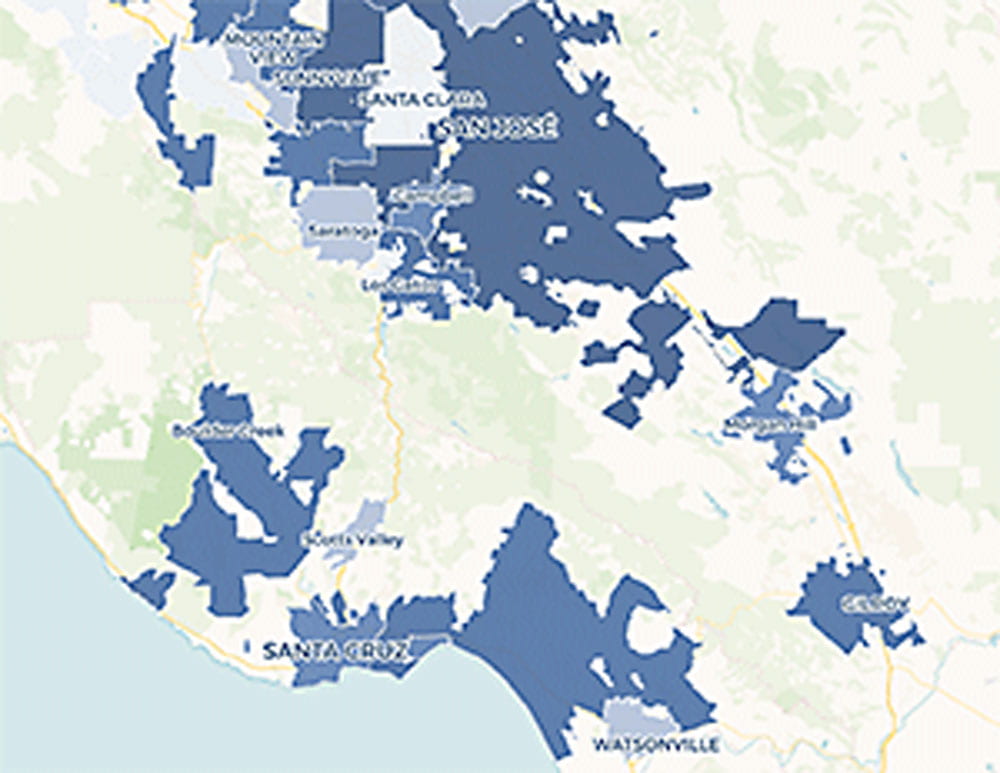

Compare our policies to those of other bay area locations using The Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley’s interactive map.

The three Ps

Reinvestment in Social Housing

Housing Trust Funds

Expansion of Linkage Fees and Bonuses

Affordable Student Housing

Land Use and Zoning

Community Controlled Strategies

Funding Cuts

Shift from Multi-Family Rental to Single-Family Home Ownership

Shift from Public to Private Sector

Financialization

Local Politics

Sources:

- The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes (National Low Income Housing Corporation, 2017)

- Bryce Covert, “The Deep, Uniquely American Roots of Our Affordable-Housing Crisis.” The Nation, May 24, 2018.

- California’s Housing Emergency: State Leaders Must Invest Immediately in Affordable Homes(California Housing Partnership Corporation, March 2018)

- California’s Housing Future: Challenges And Opportunities: Final Statewide Housing Assessment 2025 (California Department of Housing and Community Development, February 2018)

- Santa Cruz County’s Housing Emergency and Proposed Solutions (California Housing Partnership Corporation, September 2018)

- Jimmy Tobias, “Meet the Rising New Housing Movement That Wants to Create Homes for All.” The Nation, May 24, 2018

- Alex F. Schwartz, Housing Policy in the United States. Third Edition. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Schwartz, ibid.

- California’s Housing Future, ibid.

- Schwartz, ibid.

- Susan Fainstein, “Financialisation and Justice in the City: A Commentary.” Urban Studies 1-6. 2016 Special issue: “Financialisation and the production of urban space”

- Betsy Wilson interview, No Place Like Home, April 2018.

- Jennifer Hernandez, “California Environmental Quality Act and California’s Affordable Housing Crisis.” Hastings Environmental Law Journal. Volume 24, Number 1, Winter 2018

- Karen Chapple and Miriam Zuk, “Housing Production, Filtering and Displacement: Untangling the Relationships.” Berkeley IGS: Research Brief. May 2016.

- Miriam Axel-Lute, “New Program Aims to Help Community Land Trusts Get to Scale” Shelterforce, April 27, 2018